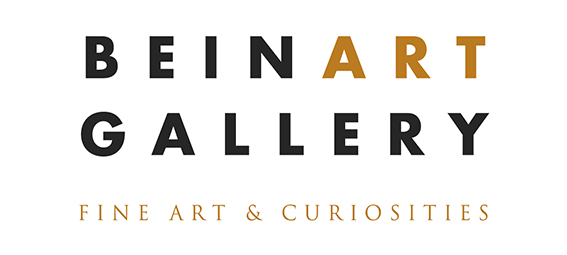

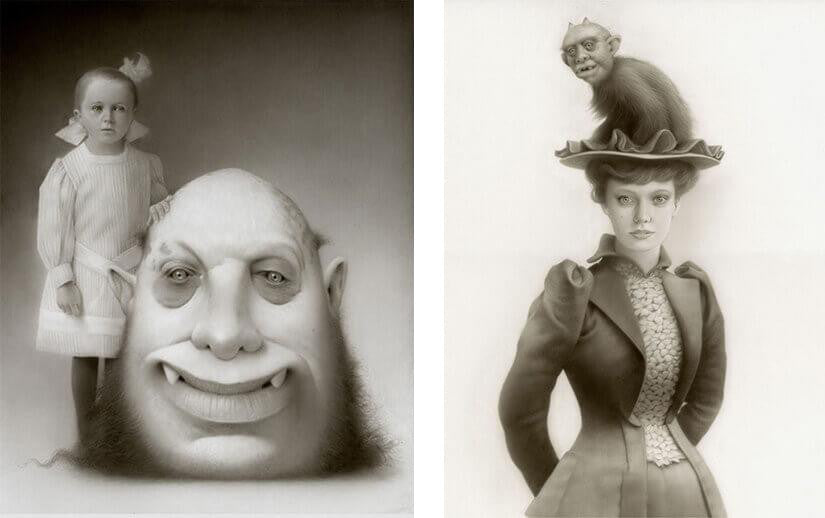

Julia & Her Swamp Friend – Acrylic painting & The Thompson – Acrylic painting.

The old-fashioned portraits rendered by Travis Louie are decidedly unlike those which might hang in the home of one’s great-grandmother. A gentle-looking monster with delicate flowers sprouting from its head, conjoined one-eyed twins sharing a single suit, a woman posed with her improbably large pet damselfly, and similar characters have “sat” for Louie, who often provides parts of their stories through the written word as well. Louie’s portraits are alternately whimsical, disturbing, and poignant, the culmination of a fertile imagination and dedicated skill.

“I think the human race is full of misunderstandings based on people holding too close to their own cultures and being unable to embrace the idea that people can believe in other things and still get along in a reasonable sort of way.” —Travis Louie

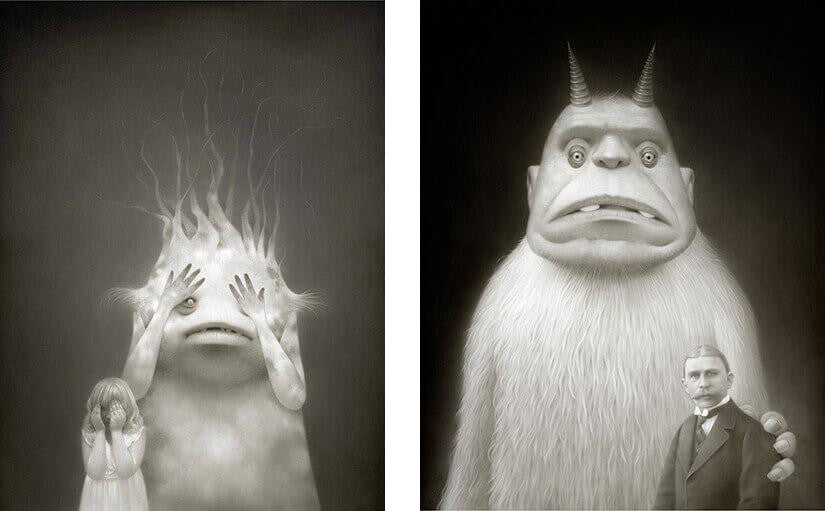

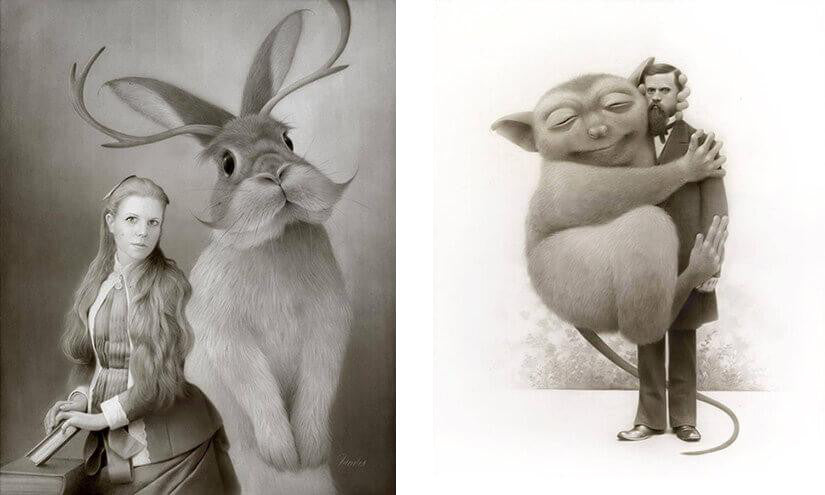

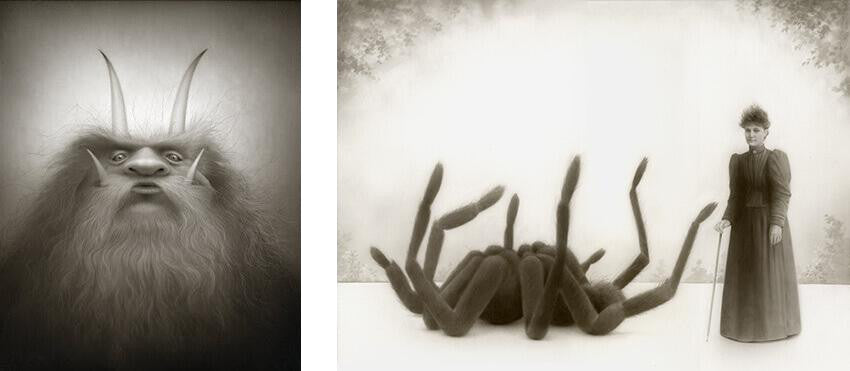

Sad Miss Bunny – Acrylic painting & The Most Dangerous Combover – Acrylic painting.

Julie Antolick Winters: How old were you when you started writing and illustrating?

Travis Louie: I have been drawing and writing stories since I was a small child. In the beginning they were more spoken-word-type stories that I would memorise. I remember my older brother wondering who I was talking to as he overheard me speaking out loud. I was 4 or 5 years old, maybe younger.

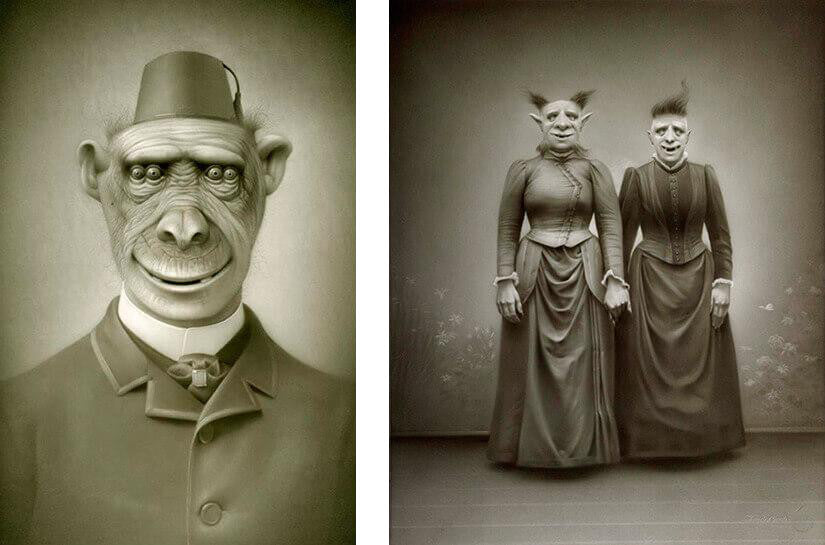

Mike, Sam & Alex – Acrylic painting & Miss Bunny – Acrylic painting.

JAW: You’ve described your work as narrative. Tell us about how a piece might come together from the germ of an idea through its execution.

TL: I'm very interested in where people are coming from. How people interact with others is a fascinating thing for me. The source material of most of my work is from people watching, a thing I like to do. I observe interesting-looking people, imagining their origins: their point of entry into society, their past lives if they came from another country, the industry or town they came from, etc. I think the human race is full of misunderstandings based on people holding too close to their own cultures and being unable to embrace the idea that people can believe in other things and still get along in a reasonable sort of way. Civility is sort of a pipe dream for me. My stories start out as little descriptions. The writings become sketches. The sketches become finished drawings, and then maybe they become paintings.

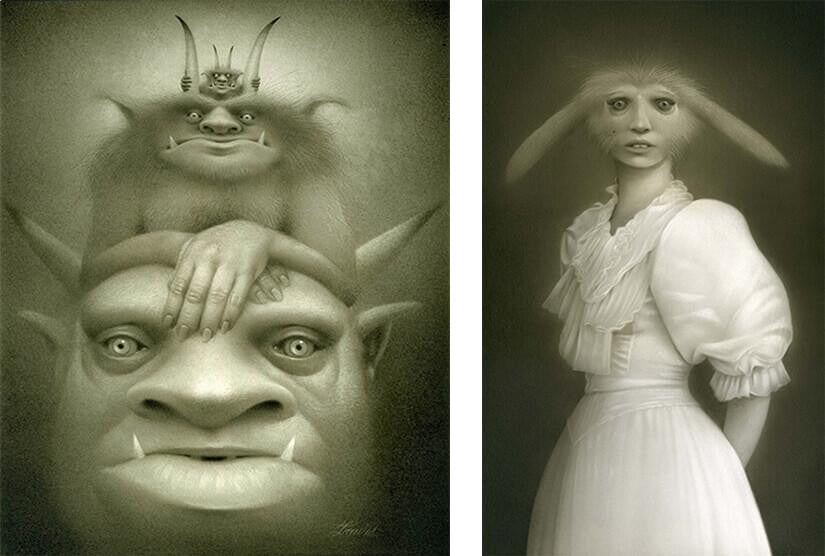

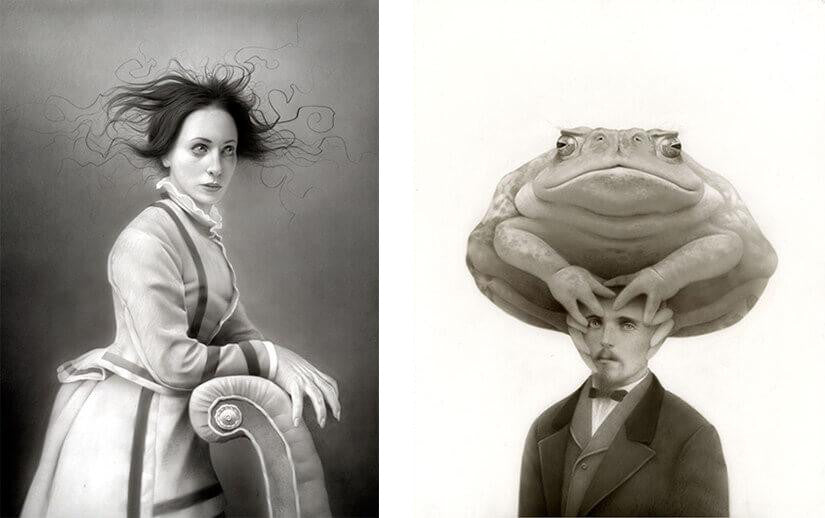

Sarah & Emmett – Acrylic painting & Henry & His One Flat Surface – Acrylic painting.

JAW: As a collector of antiques, do you ever derive inspiration from the pieces you collect?

TL: Sometimes I do. Most of the time, the things I collect revolve around old drawing tools and fine writing instruments. I'm kind of an art nerd that way. I'm always looking for different tools which make unique marks on the surface. I like to create new textures for my work.

Emily and Her Troll Head – Acrylic painting & Gremlin – Acrylic painting.

JAW: How did you develop your process of acrylic washes over graphite?

TL: The fear of "losing my drawing" with so many layers of paint when I was in school helped create the style that I use right now. When I was a young artist and my drawing skill was not up to the standard it is now, I was very conscious of making sure that I had a solid plan before I set up my painting. I would paint over a very finished drawing. These days, the structure is much looser and I allow for things to develop more organically. I'm more relaxed as I have made many changes while I'm in the process of painting. Obviously we become more confident as we gather more experience.

Young Bill at Springtime – Acrylic painting & The Bride of Stan – Acrylic painting.

JAW: I’ve read that you were very much into 1950s memorabilia as a child; you collect antiques, and your work carries a strong late-19th-century flavor. What do you suppose accounts for your abiding interest in the past?

TL: The 19th-century flavor of the work relates directly to my interest in the immigrant experience in North America from the late 18th century through the early 20th century. I chose the old 19th-century photographic motif because it made sense to me as a convincing record of such things. The interest in the 1950s comes from nostalgia for Atomic Age science fiction stories. The economic and sociological atmosphere was very different in the 1950s. I almost get that sense that people were more hopeful about the future in North America than they are now and that played into a sense of wonder that is very important to me. When I talk to young people today, I don't see as much optimism.

The Strangler – Acrylic painting & Oscar And The Truth Toad – Acrylic painting.

JAW: Of the subjects of your portraits, your website notes that “the underlying thread that connects all these characters is the unusual circumstances that shape who they were and how they lived.” Tell us more about what you’re exploring through your work.

TL: I mentioned the immigrant experience when answering one of the previous questions. Let me explain a little further. Even though I'm a few generations in this country, I still grew up as an outsider in a way. When your race or culture is not the dominant one in a particular locale, it is very obvious for people to notice. There is so much xenophobia really, and it springs from so many things: fear of the unknown, outsiders coming to take or change the prevailing culture… I've experienced a lot of racism growing up, and I still do. I created these characters as a sort of veiled commentary on racism and the immigrant experience. In many of my stories, my characters came to North America like any other immigrants, only I chose otherworldly types of beings to make the stories more universal.

Miss K and Her Jackalope – Acrylic painting & Oscar and The Giant Tarsier – Acrylic painting.

JAW: The lines of your paintings are very soft, lending a peaceful quality to your portraits even on occasions when the viewer might be alarmed by (or for) the subject. Is this intentional, to make the pieces more “friendly” to the viewer or perhaps even for yourself?

TL: Originally I made a conscious effort to create soft edges in an effort to emulate the appearance of those 19th-century photographs I collected. As I did more and more of the paintings, the technique “stuck.” I rather like having soft edges on most of the surface so that the things that I want the viewer to focus on are easier to bring to focus. Edges are very important to me.

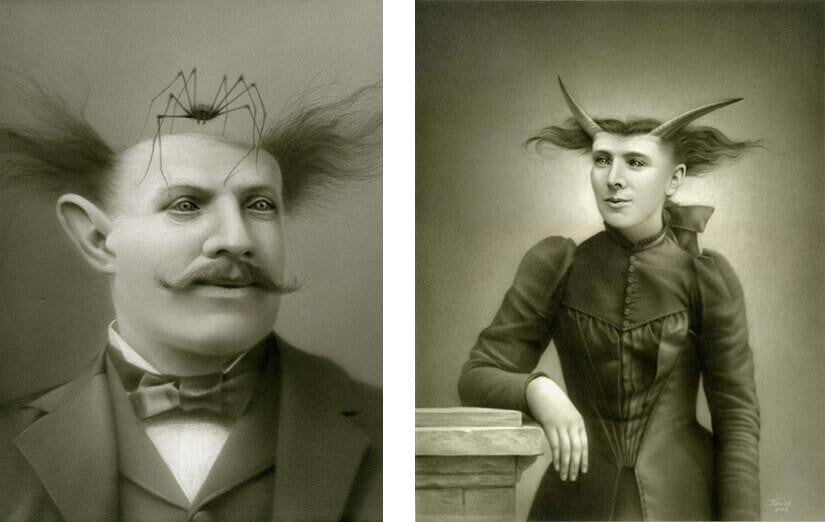

Mr Stephenson and the Bug - Acrylic painting by Travis Louie.

JAW: What is your view on the relationship between the artist and audience?

TL: Well, I'm thankful to have an audience. This is a very unusual occupation, vocation, way of life, however you want to describe being an artist of any kind. Generally, we would like to think that we create our “art” from within, in spite of whether or not an audience exists. I am very aware of there being an audience, as I get fan mail and such. It would be impolite and disingenuous to ignore the idea of an audience. I communicate with them when I can, as I'm always curious what they see in my work.

Maxo the Ultra-Chimp – Acrylic painting & Pals – Acrylic painting painting.

JAW: Regarding the stories that inspire and accompany your visual art, are they simply a springboard for your paintings, or do you play with exploring the writing more? Or is it the case that the writings in your journal are more expansive, and we just see clips that are selected to be viewed with the paintings?

TL: I enjoy writing almost as much as I enjoy painting. I love a good story, and I intend on writing more. As far as being a springboard for the paintings…they have been and sometimes not so much. I can make a painting from a very expansive story or from a few descriptive sentences (which is often the case).

The Family Yeti - Acrylic painting by Travis Louie.

JAW: You’ve noted that the advent of the Internet makes it much easier to research galleries for what types of art they exhibit than it was when you were first looking for gallery prospects in the 1990s. What other impacts of technology on “the business of art, ” for lack of a better way of putting it, have you observed? And has technology had any impact on how you make art?

TL: The Internet has made artists more accessible if they want to be. No person is an “island” unless they want to be reclusive on purpose. It has made the transfer of information a remarkably fast tool and also a place for hyperbole that makes one cringe. The ability to interact with our audience is made easier, but [doing so] requires a lot of time, so it makes us all work a little faster, I think, or at least more economical with our time. We still have to satisfy our urge to make our artworks, so we shouldn't spend too much time on the Internet.

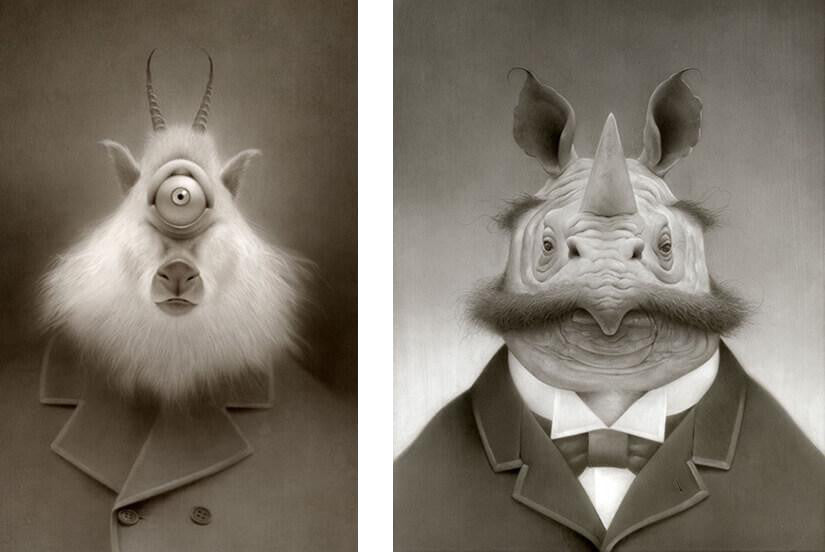

Phineas G. Gruffin – Acrylic painting & Rhinochops circa 1881 – Acrylic painting.

JAW: Has returning to art school as an instructor had any effect on how you approach your own artwork?

TL: Mostly, I am more cognisant of my time. I think it helps me work more intuitively, and maybe I seem to be able to solve design problems faster these days.

The Great Woolly Krampus – Acrylic painting & Miss Emily Fowler and her Spider – Acrylic painting.

JAW: What are the most important things you try to convey to your students about their work itself and about the art world?

TL: The art world is bigger than us, and there are always going to be people trying to control it. The attempt to control or predict the zeitgeist is a curious thing. Always stay focused. Always try to maintain a positive attitude. We do not control all the variables, but be aware of those things that are in our control. Make use of your time wisely. Don't forget where you came from. Be honest with yourself about what you are doing and how it connects to your life.

Night People (All Nightmare Long) - Acrylic painting by Travis Louie.

JAW: Is there anything you have in the works that you’d like to share with our readership?

TL: I have a show coming up in November at KP Projects MKG, previously known as the Merry Karnowsky Gallery, and I am curating a special show in project room.

Naven Overcomes his Spider Phobia – Acrylic painting & Emily – Acrylic painting.

This interview was written by Julie Antolick Winters for the Beinart Collective in 2015.

Julie Antolick Winters is a writer and editor residing in the state of Maryland, USA, in a small city near Washington, D.C. Julie cowrote the introduction for Black Magick: the Art of Chet Zar and co-copyedited this book and Kris Kuksi: Divination and Delusion for Beinart Publishing. She has also been conducting artist interviews for the Beinart Collective & Gallery since 2010. In addition to her work for the Beinart Gallery, she edits science articles and books, writes poetry and practices the art of negotiation with her son.

Cart

Cart