Scott Listfield’s paintings depict a lone astronaut exploring surreal landscapes, often evocative of apocalyptic science fiction stories. Protected from the elements, as well as from identification, the figure seems alienated in a world populated with recognisable corporate logos, pop icons, and man-made structures, often dominated by natural elements.

You’re very likely familiar with his work. His paintings have been exhibited internationally, and his concepts have attracted the attention of many publications. Even if you haven’t viewed one of his paintings with your eyes, you’re still familiar with the feeling that his works emit, which perfectly express a common cultural atmosphere we are experiencing, from a vantage point that feels safe.

It’s easy for anyone to see themselves in Listfield's spacesuit, recognising their surroundings, and perhaps feeling awed by them, yet neither able to place exactly where they are, nor feeling safe enough to breathe the air. And yet, these landscapes are stunningly beautiful and calm, showing deference to Mother Nature, and through that evoke a strong sense of hope.

This familiarity of the concepts inherent in Listfield's landscapes, combined with great artistic talent, are powerful tools to combine, perhaps conveying a message that the world needs to hear.

It’s a neat bit of synchronicity that this interview was published in November, 2019, the date in which Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner takes place, and thus falls out of our future.

Scott Listfield's debut Australian solo show, Fury Road, was held at Beinart Gallery in October 2019.

See available paintings by Scott Listfield.

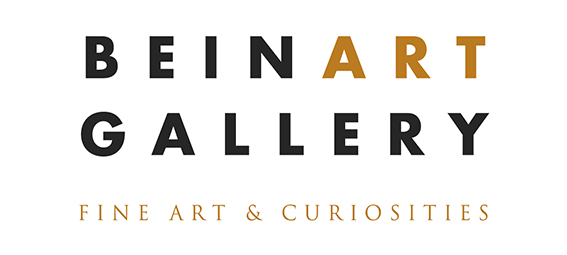

The Sea - Oil on canvas for Listfield's solo show, Fury Road at Beinart Gallery.

Samantha Levin: What was your art education like, and what kind of affect or influence has it had over your career overall?

Scott Listfield: I went to a liberal arts college in a small town in New Hampshire, which is itself a small state in the US which even some people here in the US aren't totally sure is a real place (sorry, New Hampshire). I'm not sure if “liberal arts college” is an idea which translates in the rest of the world, but it was a smallish university which specialised in overall education – in other words, it was not an art school. I took classes in psychology, anthropology, math, astronomy, etc. But there was also an art department at the school and although I had no idea what I wanted to study when I first arrived there, I quickly realised that I wanted to be an artist and so I majored in art while I was there.

Most of my professors were 2nd or 3rd generation abstract expressionists and had grown up in a world where realism and narrative based painting essentially didn't exist. They also grew up in a world where living in New York was affordable and you could make a solid career teaching art, neither of which I found to be especially true anymore. Anyhow, they were all lovely people and I have fond memories of them and they did a very good job teaching me how to think about art, if not necessarily a great job preparing me to be an actual working artist in the world as it exists now. Which I think might be typical of many other people's art education.

My education was very much in a sort of modernist/abstract academic tradition, and I realized even before I graduated that I had zero desire to paint that way. Which led to much frustration in my early art career. But, as I've realized much later in life, it might be as important to rebel against your formal training as it is to embrace it. And boy did I. If I'm being totally honest, I might have started painting astronauts at least in part because I thought it was exactly the type of thing my professors would have seriously frowned upon. Most of them have been very supportive of my career over the years, so I almost certainly was projecting feelings onto them they might not have actually held. But, as a young artist, it was important to me to carve out my own path, and it was helpful in that regard to feel like I was doing something at least slightly rebellious. At any rate, I don't make artwork anything like what any of my peers in school ended up doing, but that's OK.

I don't know that my art education had a huge effect on the way I paint or how I paint or the subject of my paintings. But I think an equally important piece of what I do is the ideas behind it, and that ability to think about what I'm doing definitely comes from what I learned in school.

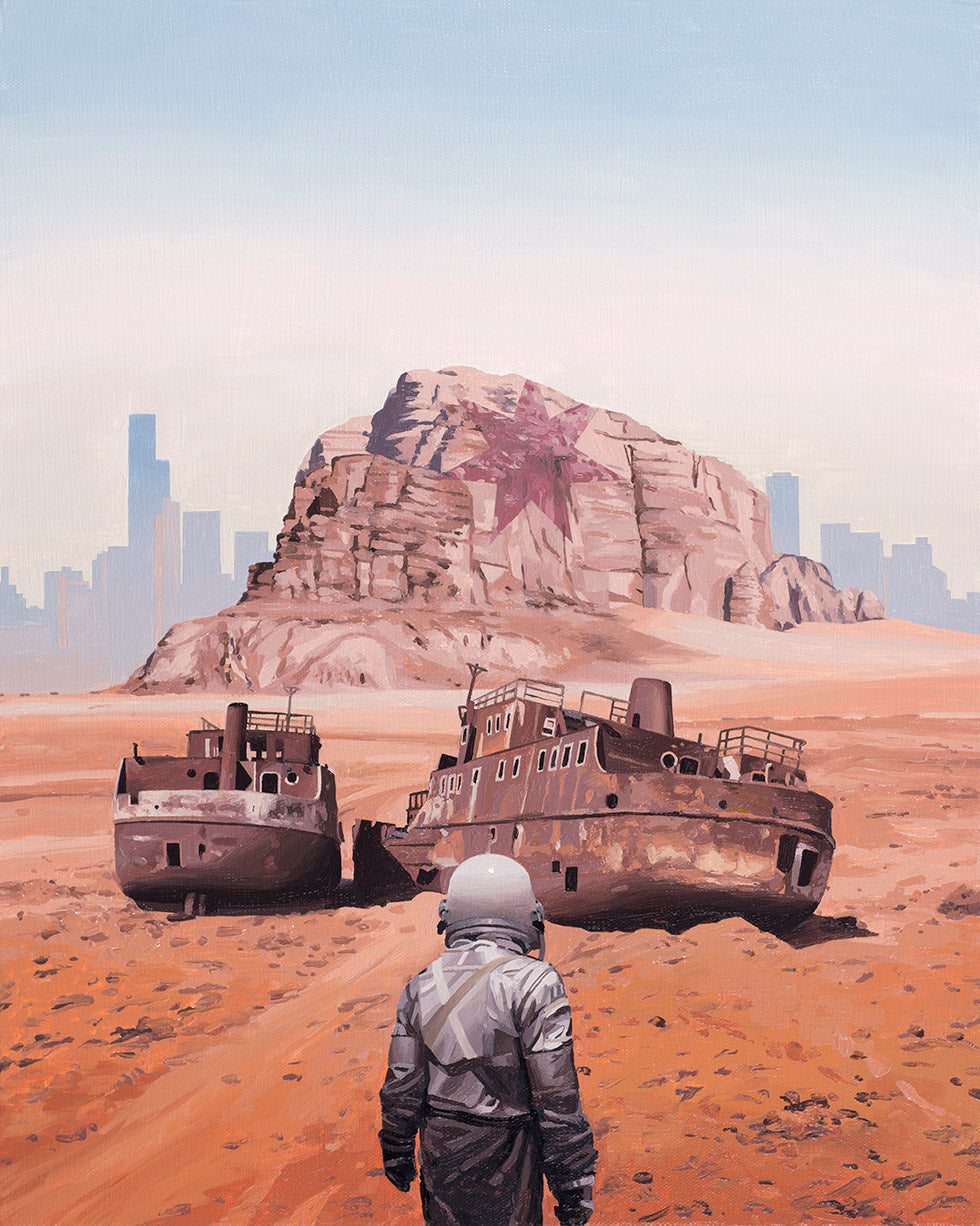

Empty Palace (Trump) - Oil on canvas by Scott Listfield.

Levin: It's wonderful that you rebelled a bit, and found your own voice, which is a hefty hurdle for artists to get over in their careers. You mostly paint in oils, right? What led you to that medium as opposed to acrylic? Have you experimented with anything else?

Listfield: Yup, I paint almost exclusively in oils, with the exception being when I do a mural, which I have done a few of. For murals, I paint in house paint, which is like trying to paint with a potato instead of a paintbrush. It's not my favorite, I guess is what I'm saying. And I paint in oils because I've always painted in oils. I like them and I never found the need to spend a bunch of time I didn't have trying other things.

For a very long time, over my early career, I worked a full time job as a designer, and I learned that the only way I would be able to do that while also making enough paintings to actually show was to cut out all the unnecessary parts of my art practice. No more farting around in the studio. No dabbling with mediums I sucked at. No experimenting with different types of paint. Which was fine. I'm kind of a creature of habit, anyways, so I never felt a strong need to step out of my comfort zone.

Billions and Billions - Oil on canvas by Scott Listfield.

Levin: What prompted you to leave your day job? Did you have a positive experience with it? I ask because I’ve heard so many disparage the artist’s decision to keep a day job, even after their work starts showing in galleries and selling, yet it’s often the thing that provides the financial stability, good health, and comforts needed for them to develop their work, and grow their career.

Listfield: First of all: yes, I liked my day job. Right up until the point when I didn't like it anymore. Because it's a day job. It's never going to be rainbows and unicorns all day. But for the most part, it allowed me to be somewhat creative during the day, to solve interesting problems and to make a living. These are extremely important things and I think many artists are too eager to leave the day job and make art full time. Which I totally get, especially if, unlike my situation, you are working a job during the day that is boring as turd.

But having a job with steady income was HUGELY important for me early in my career. It allowed me the time and space to paint anything I wanted. And let's be frank, in the early days of me making weird astronaut paintings, very few people wanted to buy them, and I had a 0% chance of making a living doing it. It's only by slowly building my art career up over years, investing a lot of time and patience into making my work better, and making my career sustainable, can I now do it full time. I was very reluctant, for a long time, to leave the safety net of a day job behind. If I had failed as an artist, and there's an insanely high probability that I would have, I would have had to go back and get a day job anyways. And to be honest, that's exactly what I did.

Leaving my day job wasn't some leap off a cliff. I grew sick of the job I had, and I had reached a point in my art career where things were going well, but it was really like having two full time jobs. Something had to break. So I stepped away from working my design job, and at first it was only for a few months, to see how it went. Let's just say, it went well. 3 months became 6, 6 months became a year, and once I realized it was sustainable, I haven't looked back.

But I'm only one bad turn from the economy away from looking for another full time day job, so I think it is, in general, not a great idea to think of it as some adversarial relationship. It's important to be realistic about the role that a day job plays in almost every single artist's life. It's only the most successful minority that never have to worry about such things.

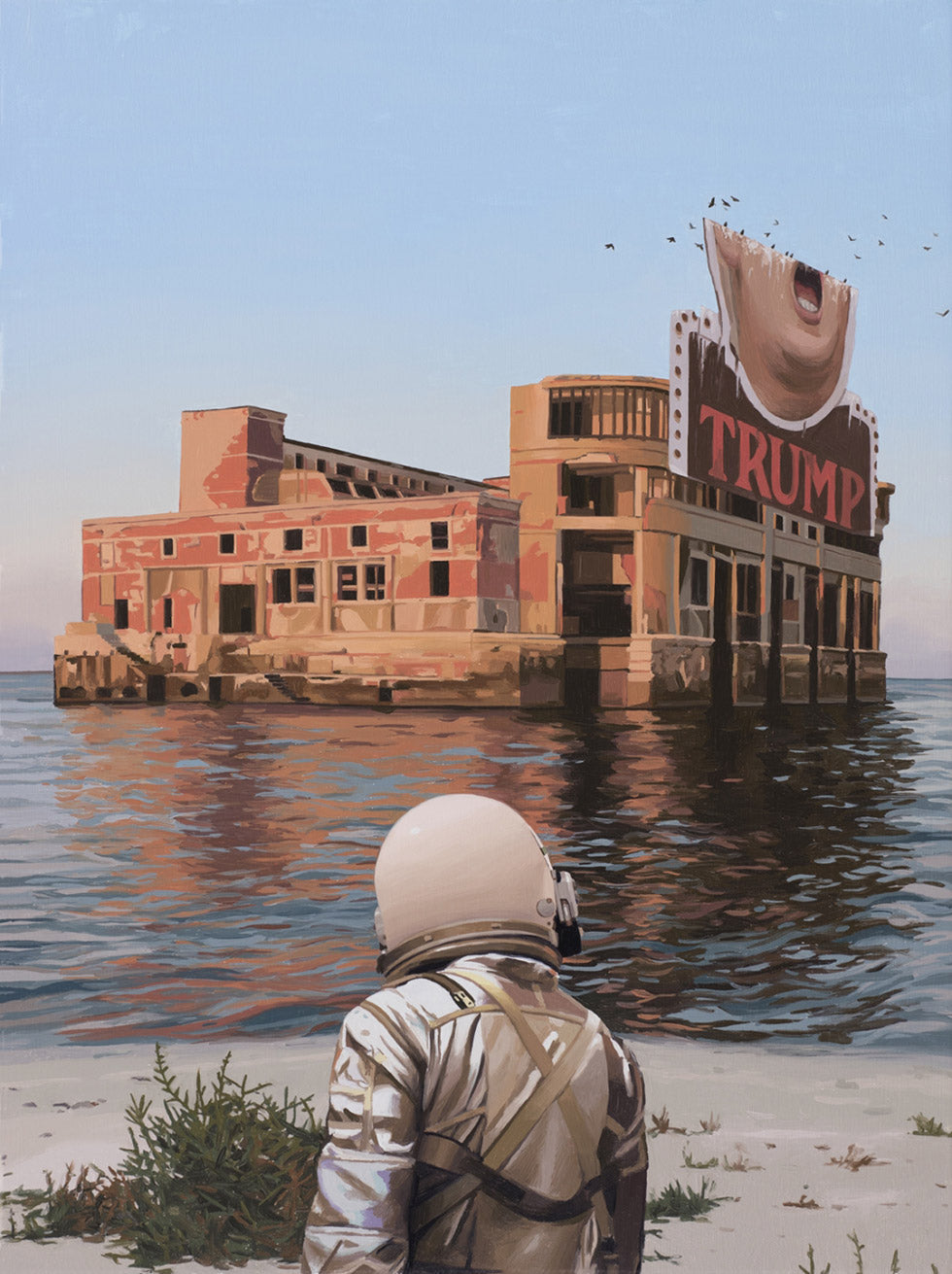

Shelter - Oil on canvas for Listfield's solo show, Fury Road at Beinart Gallery.

Levin: A gallerist in New York who I was working for once advised me that there’s a very fine and fuzzy line between responsibly taking care of yourself, and taking the risks that are necessary in order to develop a successful career in the arts. Talent is a main ingredient, of course, but so many other things need to come together, to get to the point where you can quit a day job. I think that those habits of yours that you mentioned earlier are included in that alchemy. They come through to me as clarity in your work and its voice. There's a language spoken through them that can only come from you, and I suspect that those who are familiar with your work will find comfort in that: the symbols you use and story you tell are familiar and grounding. Does that ring true?

Listfield: Well, thanks! I certainly hope so. It's always been one of the most important things to me to have a unique voice come out in my work. It's something I thought about a lot early in my career. I knew I was not, by a long shot, the most talented artist out there. I didn't go to a top art school. I didn't live in New York, I didn't have a lot of high powered connections, my work maybe didn't fit in with what was happening in the gallery scene back then.

But one thing I knew I had was a singular vision. I knew I had something to say, that no one else was saying. Of course, back then, I wasn't all that great at making the paintings convey that vision. But that's the thing about spending many years working on the same project. About making, literally, hundreds of paintings. I did get better at making them, which is nice, obviously, but I also got much much better in finding my specific voice.

Knowing what I wanted to say in my work and how I wanted to say it. Giving the work a very specific emotional voice. That's the kind of thing I definitely couldn't have done early in my career. I just didn't have the skills as a story teller. I had to hope that what I was saying would resonate with people, and that they, too, would find some familiarity in what I was saying.

In many ways I'm very lucky that it seems that they have. But it's also the payback for all those years of knowing I had something to say, and keeping at it even when there was no one listening at the time. Eventually I found my voice and, thankfully, an audience interested in listening to it.

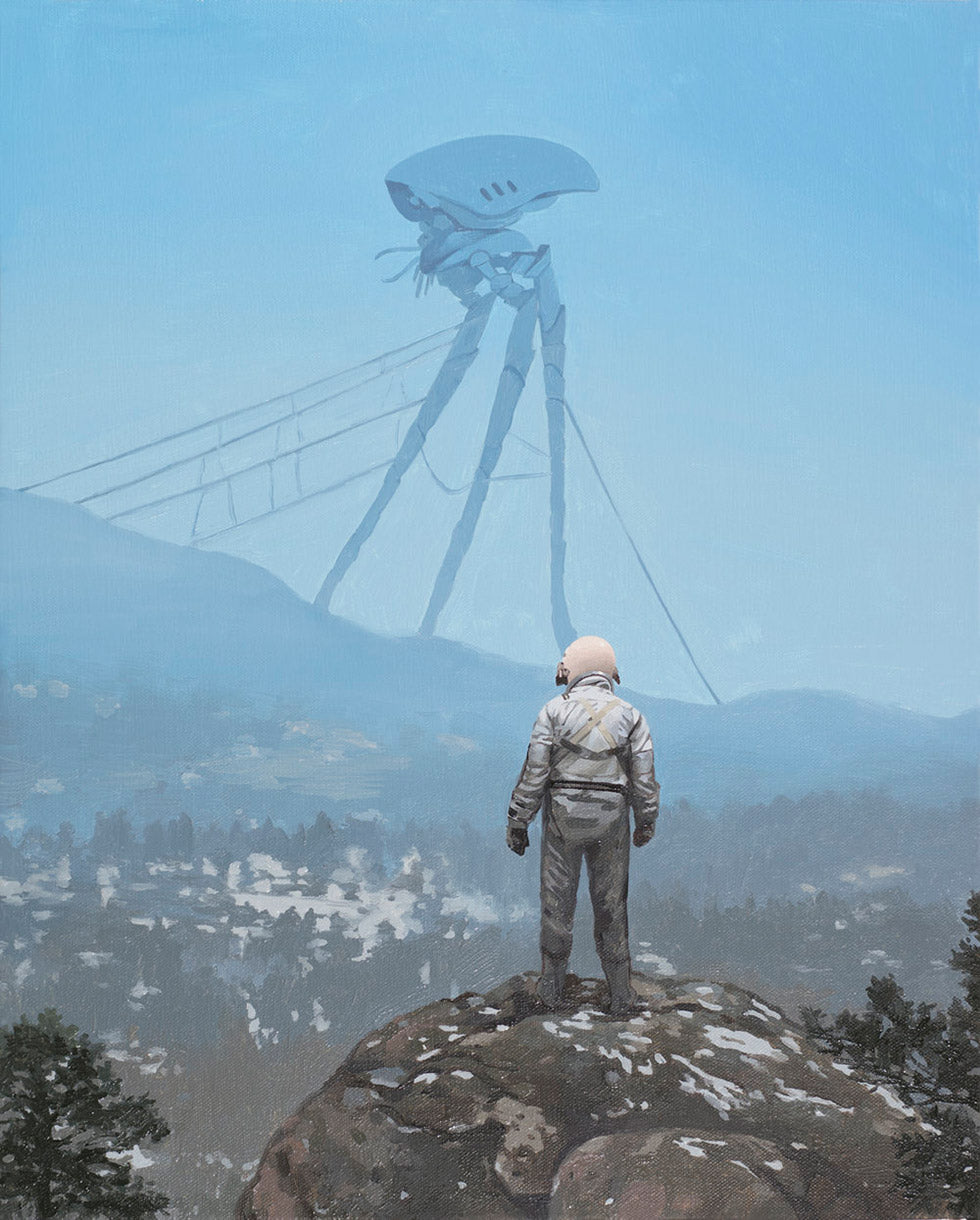

Tripod 1 - Oil on canvas by Scott Listfield.

Levin: You were strongly inspired by Kubrick's 2001 A Space Odyssey. Can you tell us how this film influenced the direction of your work? Also, are you a fan of old science fiction illustration from the 1960s?

Listfield: I previously mentioned that when I graduated from university I was left grappling with what kind of art I wanted to make, in large part because I felt a bit disconnected from the type of art I was taught to make. I spent half of my last year in school studying in Italy, I returned back to my college to finish up, and then three days after graduation I hopped a flight to Sydney, and lived there for around 6 months. Living abroad had really changed my perspective on my place in the world, while also, strangely, making me feel like I didn't quite fit in once I returned home, either. I started working an entry level job, got myself an entry level apartment in Boston, and tried my best to start being an adult, which I felt very poorly equipped to do.

Around this time I started thinking about making paintings that were almost like short stories about the world around me. About exploration, about the strangeness of the contemporary world and about the feeling of alienation as we make our way through it. I knew that I wanted there to be a recurring character in these stories, a protagonist who appeared in each one to center and ground the stories. I knew I didn't want to paint myself doing these things, I wanted it to be a much less specific character, ideally someone the viewer could easily see themselves in.

For some context, this was right around the turn of the century. The year 2000! Which sounded super futuristic back then. People were freaking out about Y2K and wondering if the world as we knew it might end. I had always thought that my 21st century future would involve flying cars and robot best friends. Instead I was living in the world's tiniest studio apartment eating single serve pizzas and watching garbage TV on my tiny television. It was at this moment that I watched 2001: A Space Odyssey for the first time.

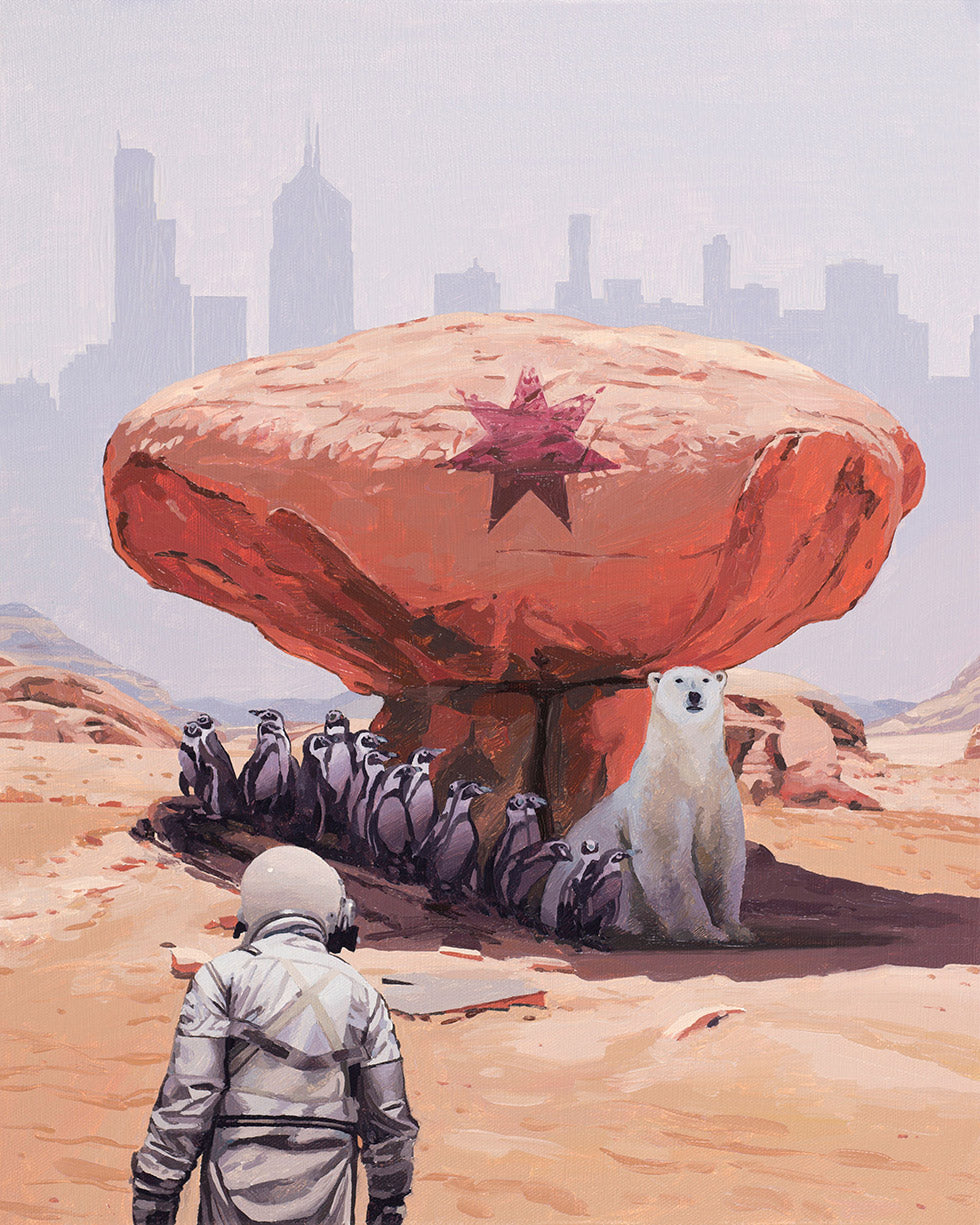

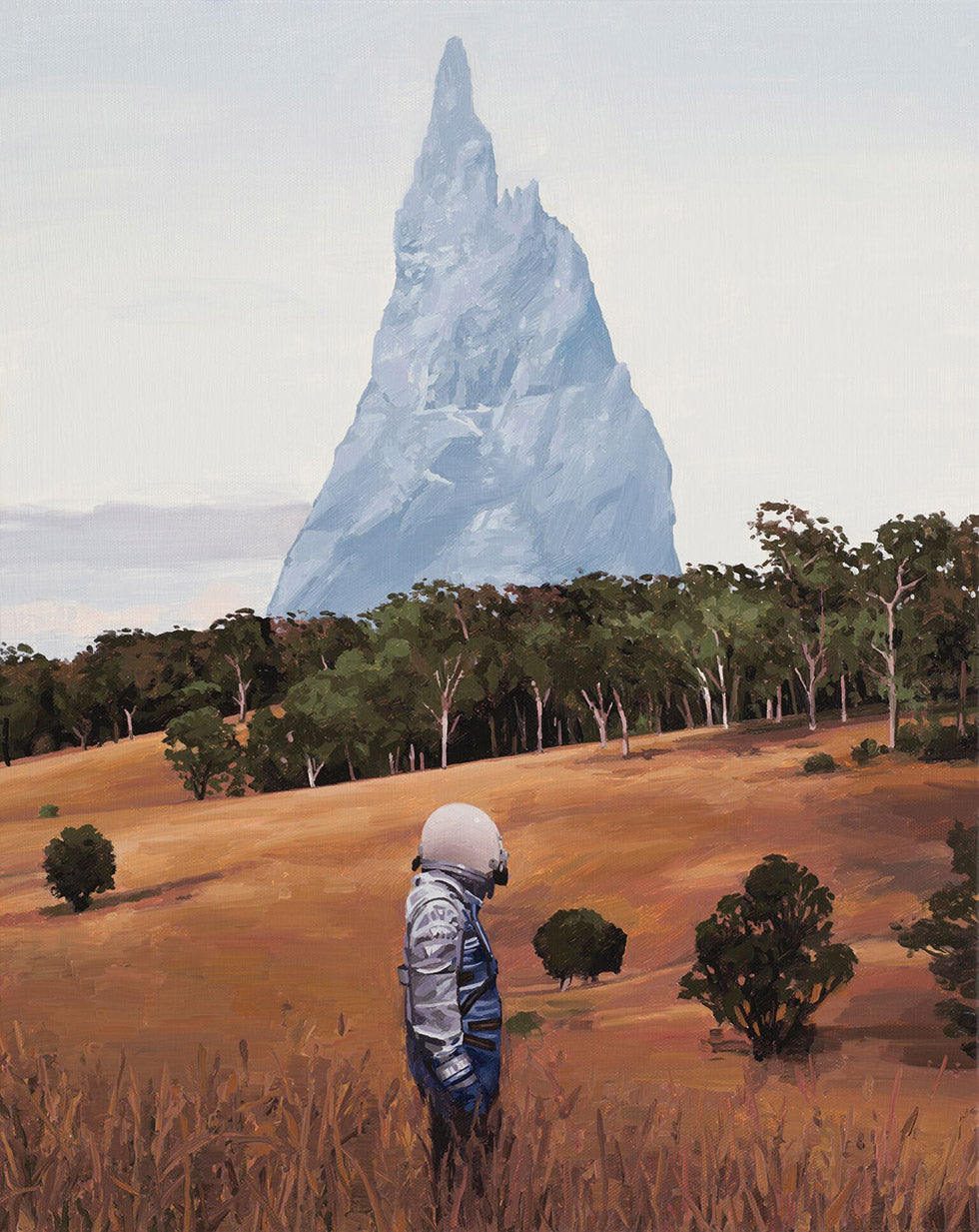

Ball's Pyramid - Oil on canvas for Listfield's solo show, Fury Road at Beinart Gallery.

And something about it struck me. The movie originally came out in 1968, and here I was, practically in the actual year 2001, and it all seemed so futuristic still. And that's when it occurred to me, watching the fictional 2001 on my crappy television. I had grown up watching science fiction movies and TV shows, reading comic books and novels, and I had expected that to be the future I would grow up into. And it was not. At all. And yet the world around me felt strange and alien still. Just not in the ways I had imagined. And so right then and there it occurred to me that this astronaut, the one from the fictional 2001, the one I had grown up all my life thinking would be a symbol of the future I would live in, that astronaut should be the protagonist in my paintings.

And so I started painting astronauts. And yes, to answer your question, when I first started I was very interested in old science fiction illustrations from the 60's. They're so unashamed of being utopian, which in my cynical 21st century brain is both extremely charming and also a little bit sad. I don't look at them much anymore though because I feel like they almost live more in the world of I Love Lucy than they do of anything contemporary. And although I was very much inspired by visions of space from the 50's through the 80's, I now spend more time thinking about our actual future and where we might be headed.

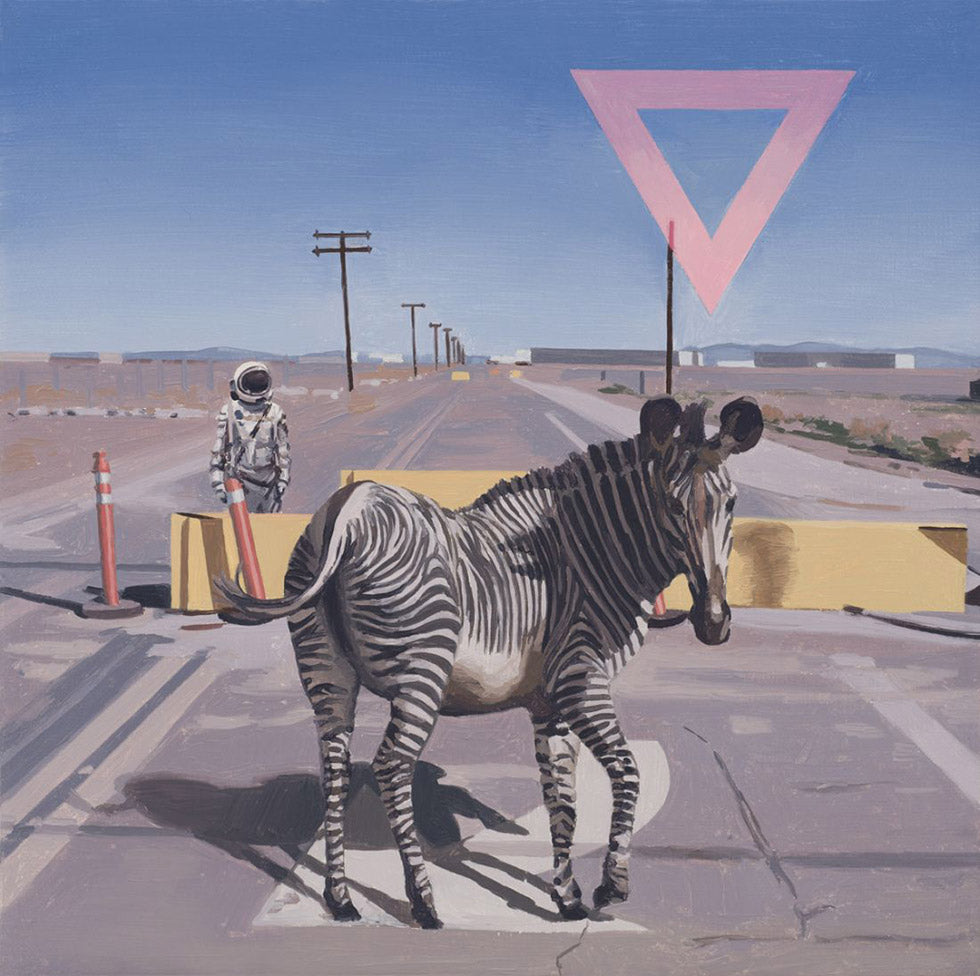

Grevy's Zebra - Oil on canvas by Scott Listfield.

Levin: The dreams of utopia that science fiction so often tried to depict for pop culture were candy-coated for sure. Your upcoming show at Beinart, Fury Road, is largely about the time you spent living in Australia, and, of course, the most recent Mad Max movie, which links to the significant post-apocalyptic theme that speculative or science fiction often explores. Tarkovsky's Solaris, and Roeg's The Man Who Fell to Earth both come to mind. While this is nostalgic for you on a personal level, I think that you’ve struck a chord. How might this upcoming body of work connect with a larger group of people? Is there a zeitgeist you’re connecting to, here?

Listfield: Well I think it has long been a human passion to think about how it all ends for us. Movie series like Mad Max and the Terminator are pretty bleak and yet regularly make hundreds of millions of dollars at the box office. I'm tempted to say that might be a more recent obsession, but hey, even the Mayans had an end date. In the 80's we were worried about nuclear destruction and now we're worried about environmental collapse.

And so while it certainly feels more timely to me to discuss topics related to the environment in my work, or to think about dystopian worlds, given the current political climate, it's also probably ALWAYS been timely to talk about such things. I mean, in addition to the films you mentioned, I'm also influenced by H.G. Wells, who was writing about how technology might ruin our world way back in the 1890's. And George Orwell, writing about political dystopias in the 1940's. And I love the movies of the 1980's which I grew up watching, like Escape From New York or War Games, which are still fun but feel vaguely kitschy now, but were genuinely kind of scary back then. It always feels like we're on the brink of some catastrophe. Maybe that's just what humans do.

Of course I'm also super interested in how the visions of the future from pop culture eventually seeps into our actual culture and become real. Like the Apple watch which was basically in Dick Tracy, or the communicator from Star Trek which is kind of an iPhone, or things from Star Wars that scientists are working on making real. I mean, people have been trying to make the self drying shoes from Back to the Future II. In some ways, this future we've found ourselves in isn't at all like the one we imagined.

But in other, weirder ways, reality has mirrored science fiction exactly because we explicitly wanted it to. There's a scene in [the US cartoon show] Rick And Morty where Rick has accidentally turned Earth into an apocalyptic hell-scape, and he and Morty bolt for another dimension, leaving his family behind to deal with it. [In this new dimension] they've created a fake TV frame and are retelling Jaws like it's an ancient tale handed down from their ancestors. I can only hope I don't find myself around a campfire someday telling the story of Fury Road because TVs and electricity have ceased to exist.

Star Blazers - Oil on canvas by Scott Listfield.

Levin: You’ve often talked about how, when you returned back to the US after living abroad in Australia, you were haunted by the feeling of being far from home, which has largely inspired the direction of your artwork; ironically you found yourself in your work. What do you think it was that made you feel this way, and how might you define “home?”

Listfield: Well, I don't want to make it sound like I was a great world traveler or anything, I spent a few months living in Italy while I was in school, then went back to college, and then spent around 6 months living in Sydney, and then returned home for a while, which was the suburbs of Boston, before eventually moving into the city. But this all happened at a very formative time in my life, when I was finishing up at university, trying to figure out what I wanted to do with my life, and then setting out extremely half-assedly into adulthood.

But I spent a lot of time traveling alone over this period of time, in countries and culture that weren't my own, and as anyone who has done that before can tell you, you do eventually get used to being “not from around here.” Maybe you don't speak the language well, or at all. Or maybe, like my time in Australia, where my grasp of English was pretty solid, but the small things that should feel totally normal seem just a little weird. I didn't recognise most of the brands in the supermarket. Every time I spoke with someone there was a brief pause as they processed my accent. I had absolutely no idea where I was going most of the time. People drive on the opposite side of the road. Why is lawn bowling on television? These are very small complaints and, in fact, often add to the fun of traveling abroad, but you just get used to things feeling unfamiliar. And then you return home and expect that feeling to go away and it doesn't.

I've since learned that this is a pretty common response to travel, especially if you've been gone for a while. So it's not anything unique to me. And it happened at a time in my life where so many other things were in flux. That was a long time ago now and I did, after some time, start to feel “at home.” I don't really know how to define that concept, other than a place where you don't have to think about all the details. You know where things are without the extra mental barrier of being lost most of the time. And, of course, I now like to actively search out that feeling of being in a foreign environment. Wandering alone in a city I don't know. It helps for my work, of course, but also I just like it. I'm just not sure I would want to feel like that all of the time.

Number 83 - Oil on canvas by Scott Listfield.

Levin: Your astronaut is pretty quiet, yet makes a pretty strong statement. Do you see your work as being subversive, and could you imagine yourself ever getting louder?

Listfield: Haha! They're paintings so I'm not sure they have a volume, exactly, but I do like to think of them as being quiet. There's something about the astronaut, with a sealed helmet on, that makes me think of these scenes happening soundlessly. Of course, the paintings are often kind of contemplative, which I think is a mood that lends itself to silence. That said, I'd like to think my work is also saying something, which requires a voice of some kind. I definitely have made a few paintings recently that I might consider “louder.” Or more specifically political.

There's a lot happening in the world right now, a lot happening in my country right now, that I don't agree with. I feel like we're headed in a sad direction. I often considered my work to be very obliquely political, and I was unsure if I wanted to comment more explicitly on things that were happening. But I'm an artist. I have a platform. I somehow have a surprising number of people following me on various social media platforms. It occurred to me that if I didn't use this platform to say something, than what was I doing this all for anyways?

And so yes, I guess I have been louder lately. But no, I don't consider either myself or my work as “subversive.” I'm not a dictionary, but to me, being subversive implies saying things loudly and aggressively that might upend the norm, that might be contradictory or insulting or deliberately inflammatory to a lot of people. As far as I'm concerned, I'm not saying anything that the majority of people aren't thinking as well. I just happen to make paintings about it.

Make America Again - Oil on canvas by Scott Listfield.

Levin: Perhaps subversive wasn't the best term to use, but your work and its platform has the potential to influence for sure. Sometimes a quiet or subtle voice can make a stronger impact than a loud one. How does it feel to have so many people following you on social platforms? It could definitely serve as an amplifier for any messages your artwork can convey. As your numbers started to grow, what were your thoughts? How does it help your career, and how has it hindered it?

Listfield: I'm not going to lie: it's a little weird. I regularly look at those numbers next to my name on Instagram and wonder, sincerely, “Who the hell are all of these people??” Of course your number of followers is not everything, and it's a dangerous path to start getting too full of yourself because of it. But it is amazing. Genuinely amazing. If you had told me 15 years ago that there would be a way for me to get my work out in front of thousands of eyeballs, IMMEDIATELY, like before a painting had even left my studio, I would have been very doubtful, and then asked how many thousands of dollars you wanted from me for this service. ALL I wanted back then was for people to look at my work. And I think now we all take it for granted that it's a free service, literally free global advertising. People complain about it all the time. And hey, rightly so. Social media has a ton of net negative effects on our society and culture. Don't get me started.

But it has also given me, a smalltime independent artist, a voice, a footprint, and a platform that is way larger than I would have at any other point in human history. I can connect with people around the world in a way that would have been completely impossible, and unimaginable, not that long ago. There's no way I could be a full time artist without that. It's a gift. But it's also a responsibility.

In recent years, as things have started to go sideways, politically and societally, I've been looking at that number next to my name and thinking “I should do something.” For whatever reason, I've been given an outsized platform to say things, and I would feel lousy about myself, looking back years from now, if I didn't use that platform to say something. And so I mostly use it to post my weird astronaut paintings and farm for likes and hearts and thumbs-ups. And to sell my paintings and to sell my prints and, yes, to build my brand (ugh). But I've gotten a bit more outspoken recently, both in my online voice, and in my work, and I'm trying to find ways to leverage both to, hopefully, do a small bit of good in the world. It's the least I can do, I think.

Doof Wagon - Oil on canvas for Listfield's solo show, Fury Road at Beinart Gallery.

This interview was written by Samantha Levin for the Beinart Gallery in November 2019..

Samantha Levin spends much of her time working as a digital curator, archivist and librarian preserving rare art- and design-related materials. Also an artist and curator, she works with Contemporary Grotesque and dark artists, curating and producing group and solo pop-up exhibitions. She currently lives and works from her Brooklyn studio with the ghost of her white marshmallow-shaped cat, Luna.

Cart

Cart