DvG 2.0 - Cardboard, florist wire & toothpicks, by Greg Olijnyk. Photo by Griffin Simm.

The typical reaction on first seeing one of Greg Olijnyk’s highly detailed, meticulously crafted sculptures is one of immediate intrigue. A feeling that quickly gives way to awe and disbelief on realizing that these mechanically precise, sci-fi influenced pieces are all made from an unlikely and humble material: cardboard.

Interested in building, construction and modelling since childhood, Melbourne based designer and sculptor Olijnyk turned his focus to creating intricate, mechanically mind-boggling cardboard sculptures in his spare time as a creative outlet.

Having only begun making and sharing these pieces with the world in the last few years it’s little wonder that he’s attracted attention with his mastery of such a little appreciated material.

About to show his work for the first time in his solo show at Beinart Gallery, Olijnyk shares how he came to develop his remarkable skill set and what goes into creating his sculptures.

The process of creation can be a very personal, even selfish, endeavour. At some point however you want to share what you are proud of with a wider audience. What gives you joy may do the same for someone else.—Greg Olijnyk

The New Neighbours - Cardboard, foam core board, tracing paper, clear perspex sheet, florist wire & LED lighting, by Greg Olijnyk. Photo by Griffin Simm.

Indigo Rawson-Smith: Hi Greg, can you start by telling us a bit about you and your art and design background?

Greg Olijnyk: I grew up in Ballarat, a regional town West of Melbourne. I guess I was drawing, playing with Lego and other construction toys as much as any other kid. I just kept at it a little longer than most, with the drawings becoming more intricate and the Lego evolving into Airfix modelling kits, the more detailed the better.

Art school at the Ballarat College of Advanced Education was next, studying painting and graphic design - because no-one thought you could make a living as an ‘artist’. My parents certainly didn’t think so! I think I enjoyed design because the devil really is in the detail. Solving visual problems in a design project helped develop particular ways of approaching a particular problem.

I transplanted myself to Melbourne where the design jobs were, and here we are in 2021, after a couple of design studio jobs and many years of running my own design business.

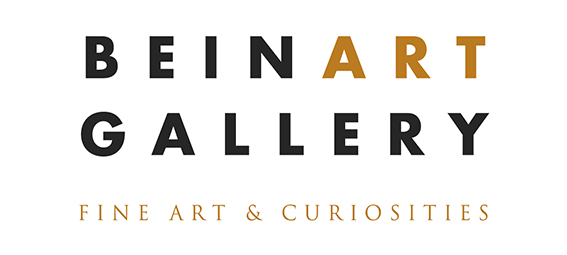

Pipe Dreams - Cardboard, clear perspex sheet, florist wire & toothpicks, by Greg Olijnyk. Photo by Griffin Simm.

IRS: Where did the fascination with robots, mechanisms and these sci-fi themes come from?

GO: Growing up in 1960s Ballarat meant being confronted with the past everywhere you looked - architecture from the turn of the century and a somewhat conservative way of thinking to match. Sci-fi is generally looking in the other direction, towards that next shiny new thing over the horizon. A promise of exciting new technology and wondrous visions of the future. Sci-fi books, films and TV shows gave us all a glimpse of that.

I was drawn to the artists who imagined such futures and made them look real: Chris Foss, Michael Whelan, Bruce Pennington, Jim Burns and later, Ron Cobb and Syd Mead. I collected books of their work and tried, unsuccessfully, to imitate it. Painting, as it turned out, was not my thing.

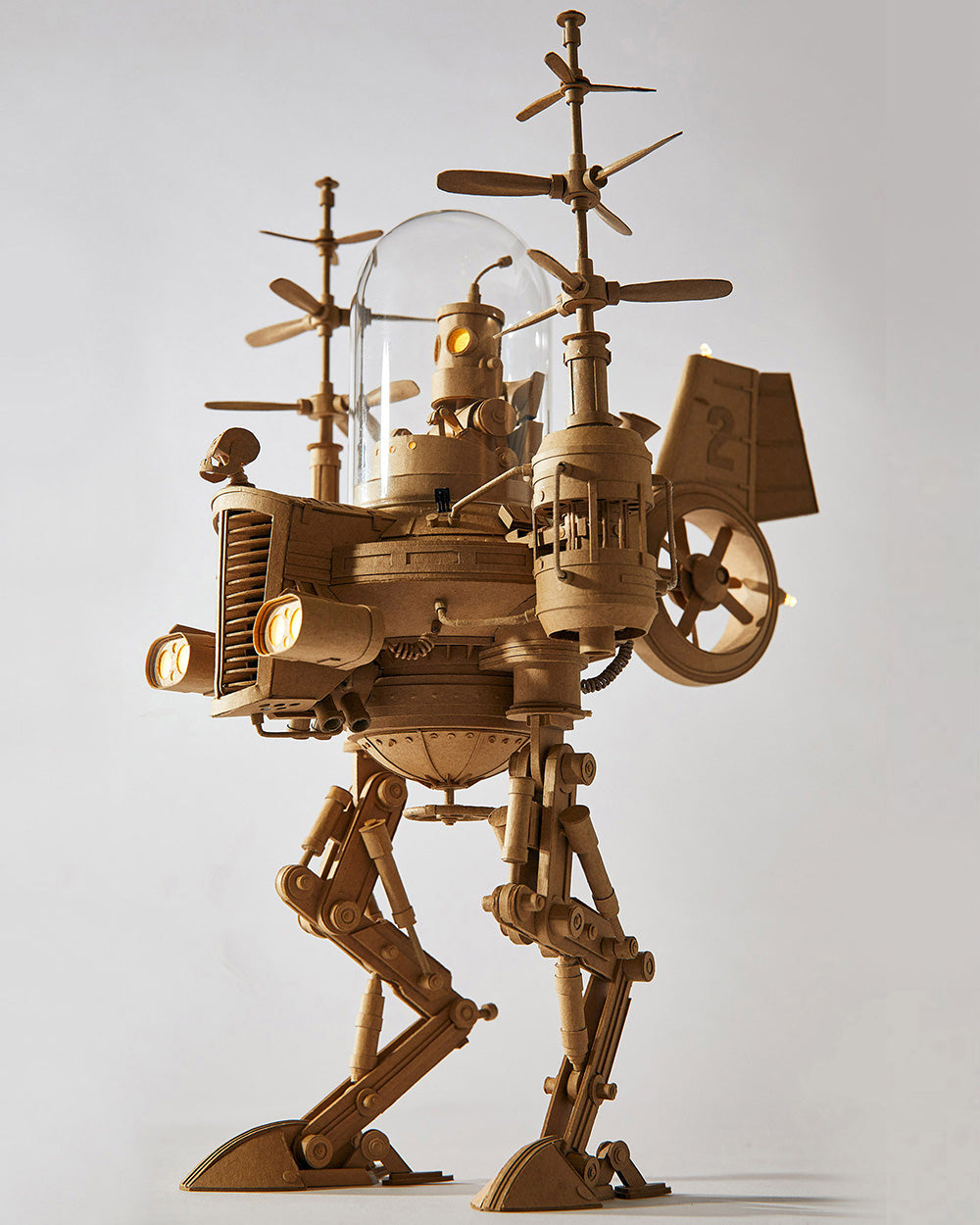

Speedybot - Cardboard, tracing paper & LED lighting, by Greg Olijnyk. Photo by Griffin Simm.

IRS: What was it that led you to use cardboard as your main construction medium?

GO: Over the years I dabbled in some form of sculpture, at one stage creating large typographical forms out of wood and plastic. But, these required power tools and a large workspace to fabricate them in. I came across work by other cardboard artists including Daniel Agdag, a fellow Melbournian, who created amazing, whimsical, detailed sculptures, and I saw an aesthetic that very much aligned with the sorts of images that had been swirling around in my head. His art revealed what was achievable using such a humble, ubiquitous material.

Cardboard proved to be the ideal medium to work with; it’s cheap, strong, flexible, easy to cut, bend, glue, fold, crease, stamp and drill. It required few tools to fashion, didn’t require a large workspace, made no noise while fabricating, produced no dust and the finished pieces weighed almost nothing. The cardboard I use now, a recycled, commercial, packaging grade card, has a rich natural colour with a subtle texture.

By using a monochromatic material, like working in marble or bronze, the uniform colour helps to focus the viewer on the form and detail. I am asked occasionally why I don’t add colour to the finished constructions. In an age of 3D printers, laser cutters and CNC machines where any imagined detail or form can be programmed and machined, the decision to leave the sculptures in their natural state celebrates the material and basically says ‘these are handmade, the imperfections, the design resolutions are there for all to see’.

The Captain - Cardboard, tracing paper, LED lighting & toothpicks, by Greg Olijnyk. Photo by Griffin Simm.

IRS: Your work involves very intricate cutting, moulding, folding and construction of the cardboard you work with. Where did you pick up these skills?

GO: When I started out as a designer in the 80s it was pre-computer. Artwork was produced manually – drawing boards, scalpel blades, glue. Packaging mock-ups for client presentations were also put together by hand. You needed to develop a modicum of cutting and assembly skills. Who knew I would be using the very same scalpel handle 30 years later, assembling cardboard robots. Several hundred hours of working with the material also helps to hone the skills a bit.

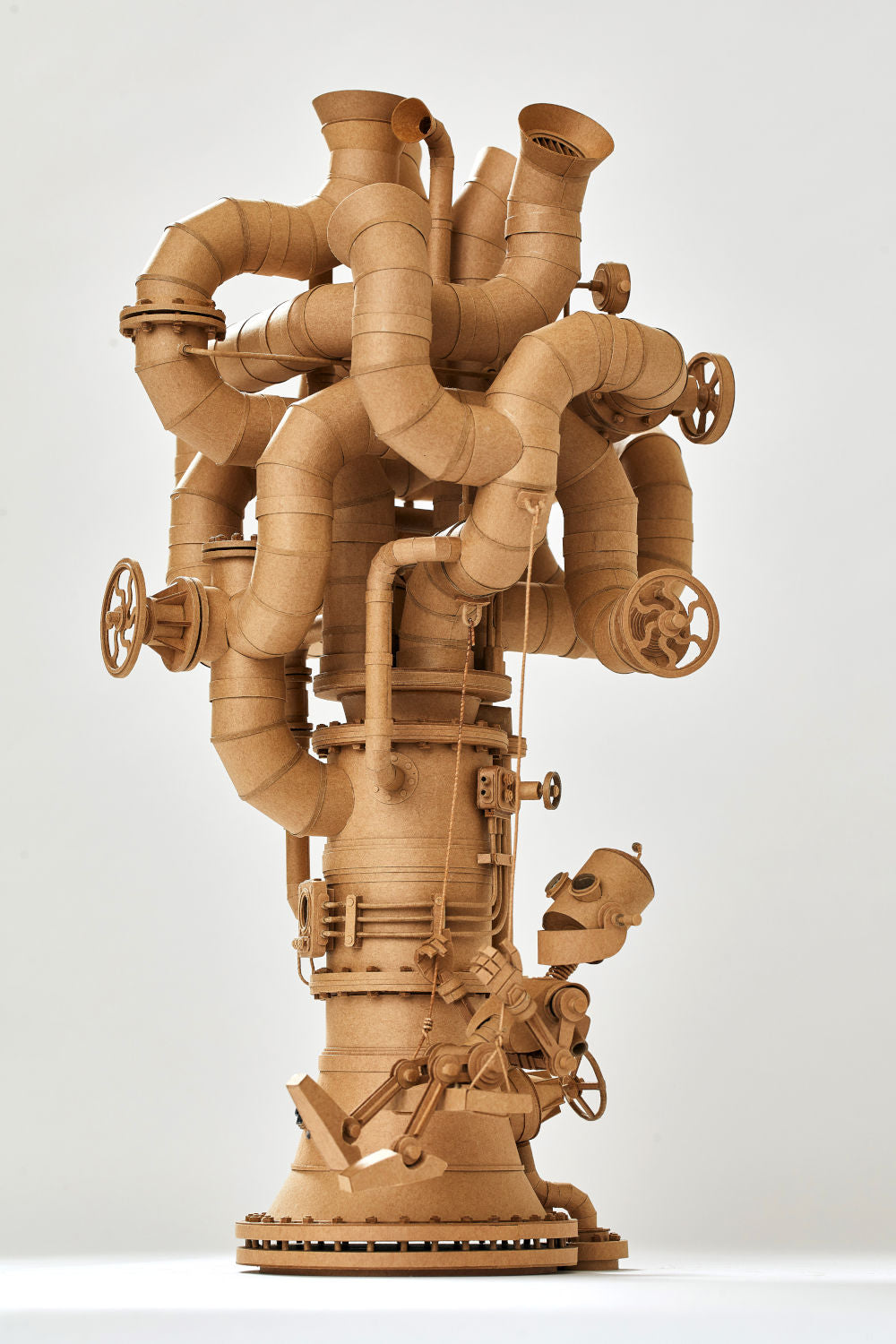

Detail of 'The Observer' - Cardboard, tracing paper, LED lighting & toothpicks, by Greg Olijnyk. Photo by Griffin Simm.

IRS: What kind of research and study is required to inform your sculptural constructions?

GO: Almost every mechanism or architectural piece I work on is inspired by a real piece of machinery or building. They all have their particular visual language. There are always details that the eye usually glosses over, but collectively add to the authenticity of a form.

A lot of research goes into every piece – how a collection of girders fit together, how do you build a fire escape, a sailing boat, an industrial robot on an assembly line? Research informs the detail and makes the final piece more believable. This then helps set the scene and create the context within which the rest of the sculpture operates. You create convincing residential apartment buildings in ‘The New Neighbour’ so that the mysterious industrial building in the middle looks more out of place.

Alan - Cardboard & magnets, by Greg Olijnyk. Photo by Griffin Simm.

IRS: Considering the intricacy of your sculptures and that you make everything as you go, with no major pre-planning or design software in sight, do you often find yourself facing obstacles in the construction process? What kind of issues do you come up against and how do you troubleshoot problems as you go along?

GO: Every sculpture has its obstacles, as does every design job. The extent of my pre-planning is generally coming up with a worthy idea to spend the next few months on. I tried planning a few pieces prior to construction but found that it just delayed the point where I started working with the cardboard. The final piece rarely looks anything like any initial sketches anyway.

I usually start with a key piece of the sculpture, a head for a robot, a cockpit for the dragonfly. Once one component is complete I can hold it, look at it in 3 dimensions and usually get an idea of how the next element will look, how the other components will flow from there.

The main obstacle is usually when there are many paths to go down, choosing from a number of directions that work equally well. I guess obstacle is the wrong word. What you are really faced with are design choices, which really is a thing all artists encounter. Occasionally I will do some pencil sketches to work out a difficult joint or piece of structure. Once the choice is made however, you are set on a path like a funnel. The subsequent choices are dependent on what has gone before until the final shape emerges at the end, sometimes as much a surprise to me as anyone else.

Of course a bit of backtracking is sometimes required, but it’s only cardboard, so any errors are easily rectified.

Alan - Cardboard & magnets, by Greg Olijnyk. Photo by Griffin Simm.

IRS: You’ve been making your sculptures for a few years now, do you find that your approach to making your sculptures, the process or the time it takes you to make them has changed at all?

GO: Not changed really, just refined. The material still dictates what you can and can’t do with it. I guess I have become quicker at knowing what processes will yield certain shapes or joints etc., but my pieces keep getting more complex and so are taking longer to complete.

It’s also a good idea to take your time when using tools with sharp, pointy bits on them.

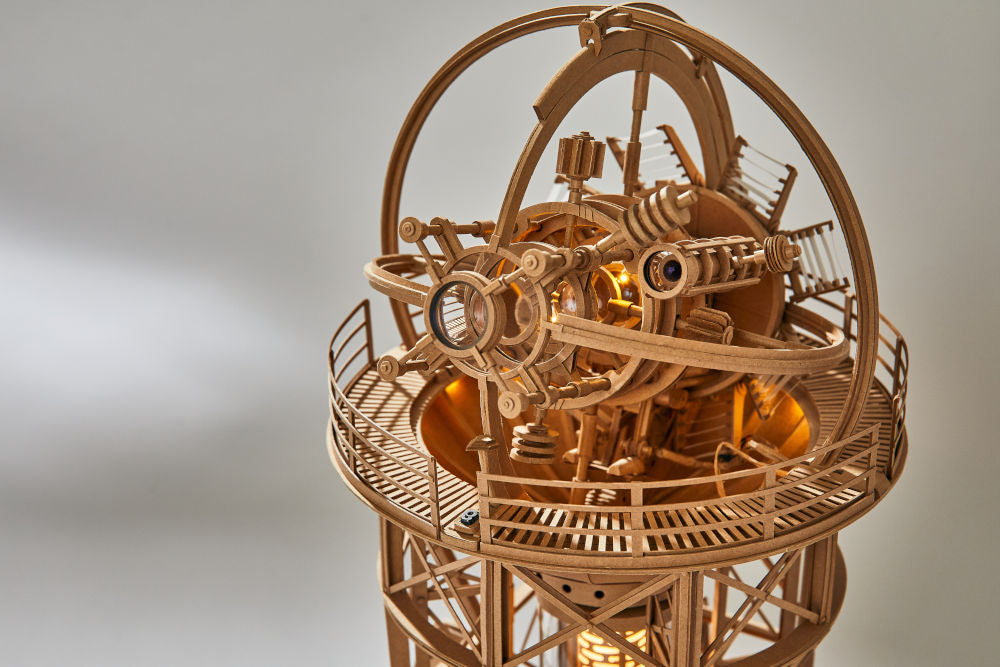

Helibot - cardboard, glass dome, toothpicks, LED lighting, motors, brass screws. Photo by Griffin Simm.

IRS: There’s a very particular aesthetic and feel to your creations, and the subjects have so much character. Was it your intention to create the feeling of continuity and narrative that people seem to see in your work, this feeling that all of your sculptures and characters have a story and exist within the same world, or has that just developed organically?

GO: I think the aesthetic has developed from the material, process and choice of subject matter, which is pretty diverse. Cardboard lends itself to simple curves, straight lines, and geometric shapes generally.

I think looking at several pieces together gives an impression that they are all linked but that wasn’t a conscious decision. The choice of a uniform construction material certainly gives everything a universal look, but the narratives that exist in some of the pieces don’t really have a common story thread.

The Observer - Cardboard, tracing paper, LED lighting & toothpicks, by Greg Olijnyk. Photo by Griffin Simm.

IRS: You’ve gained a solid following on social media and across the internet, what was it that led you to decide to share your work in person and have your first physical exhibition?

GO: The process of creation can be a very personal, even selfish, endeavour. At some point however you want to share what you are proud of with a wider audience. What gives you joy may do the same for someone else. Once completed, a piece of art becomes separate from the artist and takes on a life of its own, especially when shared (and reposted) on Instagram.

In terms of a physical exhibition, I read that sculpture exists in a slice of time and space. The act of appreciating a piece of sculpture requires the personal experience, sharing the same space as the artwork at a point in time, walking around it, discovering hidden details, experiencing the physicality of it. That’s something a JPEG on a social media site can’t completely deliver.

Assembly Line - Cardboard, tracing paper, LED lighting, toothpicks & brass screws, by Greg Olijnyk. Photo by Griffin Simm.

IRS: The title of your upcoming solo show here at Beinart Gallery is “The Contrivance”. Can you give us a little bit of insight into this title and its relevance to your work?

GO: Well, apart from the fact that titles of some shows can be a little contrived themselves, having been determined after the fact, the meaning of contrivance is ‘something contrived; a device, especially a mechanical one’ or ‘a complicated machine or piece of equipment designed for a particular purpose’. My works are certainly invented mechanical devices, and would also seem to meet the slightly more dubious definition, shared with artifice: ‘a clever strategy usually intended to deceive’. In this case the deception is that these objects pose as complex, sophisticated mechanisms yet are constructed from a common, base material that would seem to resist such manipulation.

And it sounded cooler than ‘the thing-a-me-bob’.

Dragonfly - Cardboard, tracing paper, LED lighting & metal armatures, by Greg Olijnyk. Photo by Griffin Simm.

IRS: You run your own graphic design business by day and create the sculptures in your off time, do you hope to see your sculptures become your full time focus in the future or is it something you do more for your own enjoyment?

GO: Can’t they be both? At some point I would like to spend a bit more time developing more complex pieces. It depends a bit on what the next couple of years hold.

Unibot - cardboard, toothpicks, glass lenses. Photo by Griffin Simm.

IRS: Do you have any particular ideas or concepts that you’d like to explore with future sculptures that you can tell us about?

GO: Maybe a series of life size robot heads?

The inspiration for most of these pieces has come about quite spontaneously, so you never know what might be next. I did however want to look at a few themes that I could explore, develop and build a new show around. ‘The New Neighbour’ is potentially the first in a series of sculptures that look at the stranger in our midst, the unsettling, mysterious presence next door.

The New Neighbours (by dark) - Cardboard, foam core board, tracing paper, clear perspex sheet, florist wire & LED lighting, by Greg Olijnyk. Photo by Griffin Simm.

This interview was written by Indigo Rawson-Smith for Beinart Gallery in July 2021.

Indigo Rawson-Smith wears many hats, most notably as a Gallery Assistant at Beinart Gallery, Jeweller for her brand Indigo Nox Jewellery, and as a devoted snack enthusiast.

Having spent a few years working in galleries and art spaces around London she relocated to Melbourne to undertake full-time study in jewellery design, becoming a member of the Beinart Gallery crew in early 2021.

In a year when we’ve all felt the touch of isolation and find ourselves forgetting how to speak to people outside of our COVID safe “bubbles” Indigo has been attempting to polish up her rusty social skills while interviewing a number of Beinart Gallery’s exhibiting artists.

Cart

Cart